I am working for an organization called ICAP, the International Center for HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Programs (yeah, so they got a little creative with which words to include in the acronym), that is supported by Columbia University. For those of you who feel like doing your own research, you can go to their website is http://www.columbia-icap.org/, where you will see that ICAP “works with host countries and other organizations, principally in sub-Saharan Africa, to build capacity for family-focused HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment programs”. In Mozambique, this translates into ICAP supporting the Ministry of Health and government health centers (clinics and hospitals) in their efforts to roll out ART (Anti-Retroviral Therapy, or TARV in Portuguese). And within the ICAP-MZ team there is a group dedicated to Adherence (i.e. people taking their TARV correctly) and Psychosocial Support. This is the group that I work with.

A little background for those of you who don’t eat, breathe, and sleep public health....helping a country provide ARVs to its HIV+ citizens is no simple task. Because taking ARVs is no simple task. The pills must be taken (generally) every twelve hours (so twice a day, always at the same times), and once you start on ART, you have to continue the treatment for the rest of your life. ARVs often cause side effects, and some of the medications have dietary restrictions/requirements. And...as if all of that doesn’t make things complicated enough....you have to take 95% of your doses (correctly) for the treatment to be effective. And even then, you aren’t guaranteed that it will work – drug resistant strands of HIV are popping up all over the place that no longer respond to the more commonly used medications, making treatment that much more expensive and complicated. An important thing to note....drug resistant strains are one of consequences of people not taking their ARVs correctly. So clearly, it is very important that they do so.

And that is where we come in. Our job is to try and figure out how to improve people’s adherence levels. Also no simple task. Especially in a country where there is a terrible shortage of health care workers, a poor health care infrastructure, a huge amount of stigma associated with HIV/AIDS (to give you an idea....many people hide their HIV status from their families – including from their spouses – when they find out they are HIV+), and a health care system that was designed to treat people and sent them home (not to follow their care forever).

So what have I been doing? Most of my work thus far has revolved around two things. The first is a patient tracking and tracing system. This is part of a country-wide effort to shift the health system from one that is focused on simply treating a patient and sending them away, to one that can monitor a patient’s care and treatment over time (all of this in response to HIV/AIDS). What this tracing and tracking system tries to do is enable a clinic to know when a patient didn’t show up for a scheduled appointment (could be with a doctor, with a counselor, in the TB clinic, etc.) or to pick up their medications, identify that patient, and attempt to bring them back to the clinic by sending someone out into the community to find out why they didn’t come when they were supposed to.

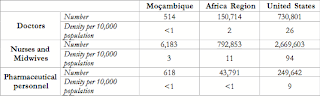

As I already mentioned, this country has an enormous shortage of health care personnel. In fact, the situation is so bad that I felt the need to look up some World Health Organization statistics to give you guys an accurate picture of the problem (and if there is one thing I have learned thus far in grad school, it is the exact location of this kind of data on the internet). I’ll even make you guys a little table (heaven forbid anyone forget what a huge nerd I am while I am gone)....

**note....I wrote this in a word document originally, and I did in fact make a table. However, it didn't quite work out when I cut and pasted it onto the blog. But not to worry.....I put my table into a powerpoint document, saved it as a picture, and was able to upload it....so enjoy.

Compared to the rest of the Africa Region, Mozambique is looking pretty pathetic. And compared to the US.....well, let’s be honest....there is no comparison there. And don’t we (in the US) currently have a shortage of health care workers? Right. Point made.

With so few medical professionals in the country, I think it’s pretty obvious that you are not going to be able to send them out looking for every patient who misses an appointment. Especially when you throw in the fact that finding patients in the community is no simple task. Communities aren’t quite put together like they are in the states....people here often have no street name or house number. In fact, when patients fill out their addresses on their medical forms there is actually a big empty space for them to include “reference points to help locate your house” (like, next to the house with the big cashew tree.....or behind the methodist church......or by the barber shop that’s painted green.....you get the idea).

So who’s going to go looking for the house next to the big cashew tree or the green barber shop? HIV/AIDS activists (or peer educators). These are HIV+ patients who go through a one or two week long training that covers a variety of topics related to HIV/AIDS (from basic medical info about the disease to counseling techniques to facts about treatment, etc) and work in clinic waiting rooms with patients who have just learned their HIV status to provide them with information, answer their questions, share their own personal stories and struggles, and to listen. In clinics that have patient tracing and tracking systems up and running, these activists are also the ones that go into the community to try and recover patients who have gone missing from care and treatment. And this has implications for how the system is put together and how data are collected, as most of these activists have limited formal education and aren’t used to having to record information on spreadsheets. Throw in the lack of material resources (paper, photocopy machines, pens, etc.) and you really have to make things as simple and short as possible.

But we have to monitor this system in order to know whether or not it is working, as well as why patients are dropping out of treatment so that we can prevent that from happening in the future. Which means we have to collect data on how many people are not showing up when they are supposed to, why, if someone went to look for them, if they were found, and whether or not they came back. It’s amazing how many forms are required to collect that kind of information....as I have been discovering over the past 6 weeks. I have been working to develop the data collection instruments for this system, as well as the data collection instruments for monitoring the activities of the adherence and psychosocial support staff at the various clinics. In other words, I am now an expert at making tables in Microsoft Word and Excel (perhaps another reason for the table above).

The other major component of my work revolves around a research study that ICAP-MZ is hoping to carry out. The study is part of an advocacy effort to convince the Ministry of Health that, considering the dearth of health care professionals in this country, it behooves them to consider formalizing the use of lay people in the health care system – i.e., peer educators/activists (which thus far they have refused to do....most peer educators are supported by international NGOs). The study goal is to determine the impact that home visits by peer educators have on adherence levels among patients....i.e., if you send a peer educator to a patient’s home every other month to check up on them and provide them with support, will they have better adherence levels? We think the answer is yes, and that the Ministry of Health should officially recognize peer educators within the health care system. I’ve been working with my boss to develop what exactly these home visits will involve, and how they will be measured and monitored.

All in all....very interesting stuff!

No comments:

Post a Comment